Modern Art & Ideas, Certification link.

Modern art - MoMA : many artists began exploring dreams, symbolism, and personal iconography as avenues for the depiction of their subjective experiences. Challenging the notion that art must realistically depict the world, some artists experimented with the expressive use of color, non-traditional materials, and new techniques and mediums.

- Places and Spaces: Exploring how art interacts with different environments.

- Art and Identity: Examining how art reflects personal and cultural identities.

- Transforming Everyday Objects: Looking at how ordinary items are reimagined in art.

- Art and Society: Understanding the relationship between art and social issues.

Additional Readings & Resources of MoMA

1. Places and Spaces

“Something that I often do is try and give those places and spaces that have never really had a place in the world some sort of authority, and some sort of voice.” — Rachel Whiteread

Different ways that artists represent place and use materials from their environment:

The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh.

Vincent van Gogh produced emotional, visually arresting paintings over the course of a career that lasted only a decade. Nature, and the people living closely to it, first stirred his artistic inclinations and continued to inspire him throughout his short life. But rather than faithfully depicting his surroundings, he painted landscapes altered by his imagination, including The Starry Night. Van Gogh was seeking respite from plaguing depression at the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy in southern France when he painted The Starry Night. It reflects his direct observations of his view of the countryside from his window as well as the memories and emotions this view evoked in him. The steeple of the church, for example, resembles those common in his native Netherlands, while the mountains in the background describe those in his surrounding landscape.

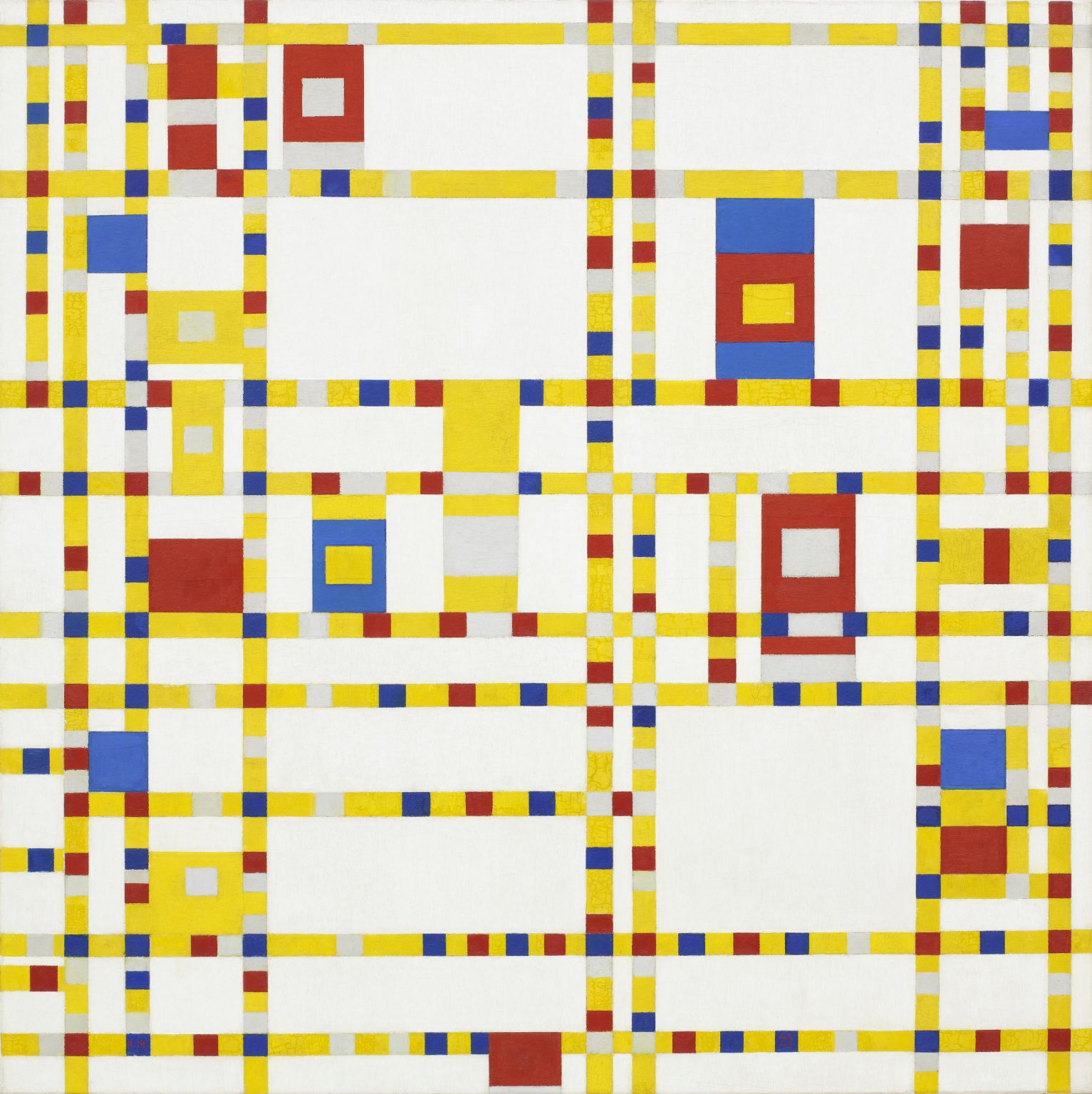

A vision of New York City filtered through the abstraction of Piet Mondrian.

In the fall of 1940, Dutch-born artist Piet Mondrian left his adopted city of Paris for New York to escape the Nazi takeover of France. In Europe, he had established himself as one of the pioneers of De Stijl, a form of abstraction that renounced naturalistic representation in favor of a stripped-down formal vocabulary consisting of straight lines, rectangular planes, and primary colors (red, blue, and yellow) meant to create visual harmony and restore order and balance to everyday life. Painted decades later, Broadway Boogie Woogie still reflects the De Stijl aesthetic—but jolted by Mondrian’s enamored response to New York City and his love of the boogie-woogie jazz music that flourished there. Claiming, “The emotion of beauty is always obscured by the appearance of the object. Therefore, the object must be eliminated from the picture,” he captured the city’s buildings, lights, crowds, traffic, and the rhythms of its jazz music in an abstract language of colored squares.

Bingo: Gordon Matta-Clark’s sculpture made from pieces of a demolished home

Unlike most architects, who would be inclined to renovate old buildings or replace them with new ones, Gordon Matta-Clark used his training in architecture to dismantle buildings—including a derelict house in Niagara Falls, New York—and transform them into works of art. Once thriving, this town had lost its luster by the 1970s. Matta-Clark saw in its abandoned homes an opportunity to practice what he called “anarchitecture”—a combination of anarchy and architecture—through which he drew attention to non-functional or overlooked buildings, architectural sites, and spaces. With a small team of workers, he cut the house’s northern façade into nine equally sized rectangles so that it resembled a bingo game card, after which this work is titled. He left the central rectangle on the house, deposited five in a nearby sculpture park where he hoped they would be reabsorbed into the earth, and kept three, which are now in MoMA’s collection. These are displayed aligned on the gallery floor so that viewers can walk around them and see segments of both the interior and exterior of the house. By inserting pieces of the outside world into an art museum, Matta-Clark hoped to draw attention to the troubled state of a real world place and its affected residents.

Norman Lewis. City Night

Lewis’s paintings, like those of many Abstract Expressionists, straddle the boundary between abstraction and figuration. The predominantly dark palette of this work evokes the nocturnal cityscape of the title; the delicate lines that crisscross the surface have been interpreted as laundry lines or power lines. In City Night Lewis has transformed this quotidian subject matter into an atmospheric and luminous abstraction. “The elements of painting constitute a language in themselves,” the artist wrote in 1949; the dynamic interplay of light and dark in City Night demonstrates his deft control over the medium.

Andrew Wyeth. Christina’s World

Andrew Wyeth painted the landscape, objects, and residents of only two places: his lifelong home village of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and the area around the neighboring coastal villages of Port Clyde and South Cushing, Maine, where he spent summers. Anna Christina Olson, who appears in this and many of his other paintings, was Wyeth’s neighbor in Maine. A neuromuscular disease had left her unable to walk. When he saw her dragging herself home one day across her family’s yard, he was inspired to make a painting conveying her indomitableness. He did this by combining direct observation with imagination. While he faithfully depicted her fragile arms and hands, for example, he replaced her family’s small yard with a vast field. “Christina’s world is, because of her physical handicap, outwardly limited—but in this painting I tried to convey how unlimited it really is,” he once wrote.

Salvador Dalí. The Persistence of Memory

With its uncanny, otherworldly feel, and its melting pocket watches and mollusk-like central figure strewn about a barren landscape, Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory seems wholly imaginary. In fact, it sprang not only from the artist’s imagination, but also from his memories of the coastline of his native Catalonia, Spain. As he once explained: “This picture represented a landscape near Port Lligat, whose rocks were lighted by a transparent and melancholy twilight; in the foreground an olive tree with its branches cut, and without leaves.” Dalí applied the methods of Surrealism, tapping deep into the non-rational mechanisms of his mind—dreams, wild imaginings, and his subconscious—to generate the unreal forms that populate this painting. These blend seamlessly with features based on the real world, including the rocky ridge in the painting’s upper-right-hand corner, which describes the cliffs of the Cap de Creus peninsula.

Rachel Whiteread. Water Tower

“Something that I often do is try and give those places and spaces that have never really had a place in the world some sort of authority, and some sort of voice,” sculptor Rachel Whiteread once explained. Among the objects that have captured her attention are the ubiquitous yet easy-to-overlook water towers dotting New York’s skyline. Though these rooftop structures once held water for the city’s buildings, they are now falling out of use. On commission for the Public Art Fund, Whiteread decided to highlight the presence of these towers. Using translucent resin—which she chose for its evocation of water and ability to capture and take on the changing light of the sky—she made a cast of the interior of a cedar water tower (a space we would otherwise never see) and then installed it on a rooftop in Soho, a neighborhood characterized by low-rise buildings.

Edward Hopper. House by the Railroad.

Painter and printmaker Edward Hopper produced closely observed urban views, landscapes (largely of New England), and interior scenes—all either devoid of or sparsely populated by people. Though he insisted that his paintings were straightforward representations of the real world, their overall sparseness imbues them with a sense of loneliness, estrangement, and stillness. Light, whether from electric bulbs or the sun, defines the places he depicts and shapes the mood of his works. A late afternoon glow pervades House by the Railroad, which features a grand Victorian home fronted by the tracks of a railroad. The tracks create a visual barrier that seems to block access to house, which appears moored and isolated in the surrounding empty landscape. Its old-fashioned architecture and lack of any sense of occupancy imply that the house may be a relic of tradition, lonely and forgotten in the push towards urbanization and progress, as suggested by the railroad tracks.

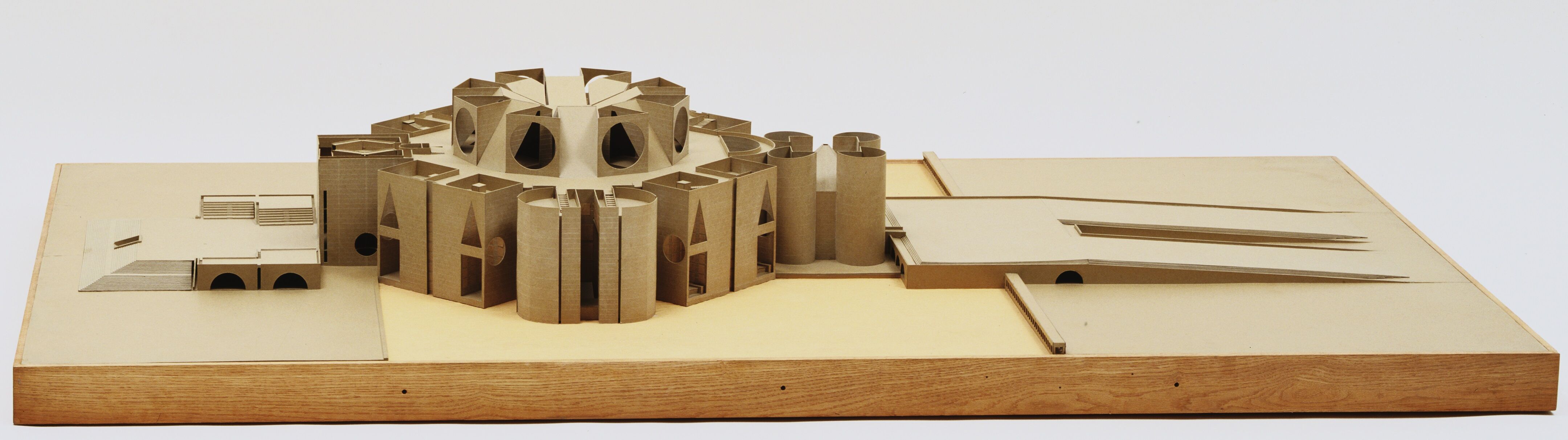

Louis I. Kahn. Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Capital of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

The construction of Louis I. Kahn’s Sher-e-Bangla Nagar (the city of the Bengal Tiger) unfolded over the course of 20 years in a radically shifting political context. Kahn was a lauded architect known for his monumental buildings when the Pakistani government commissioned him in 1963 to design a governmental and civic complex incorporating a national assembly building, a mosque, residences, offices, a dining hall, courtrooms, a hospital, a museum, and schools. It was to be situated in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and was begun when that country was still a part of Pakistan. In addition to functioning as the political center of Pakistan’s second capital city, it was meant to stand as a symbol of national unity. Kahn addressed these goals by designing a monumental structure based on square, circular, and triangular shapes and permeated with apertures that allow light to flood its grand interior spaces. In 1971, Bangladesh won independence from Pakistan. This inevitably changed the purpose of Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, which would not be completed for another 12 years, and it became instead an emblem of a newly independent nation.

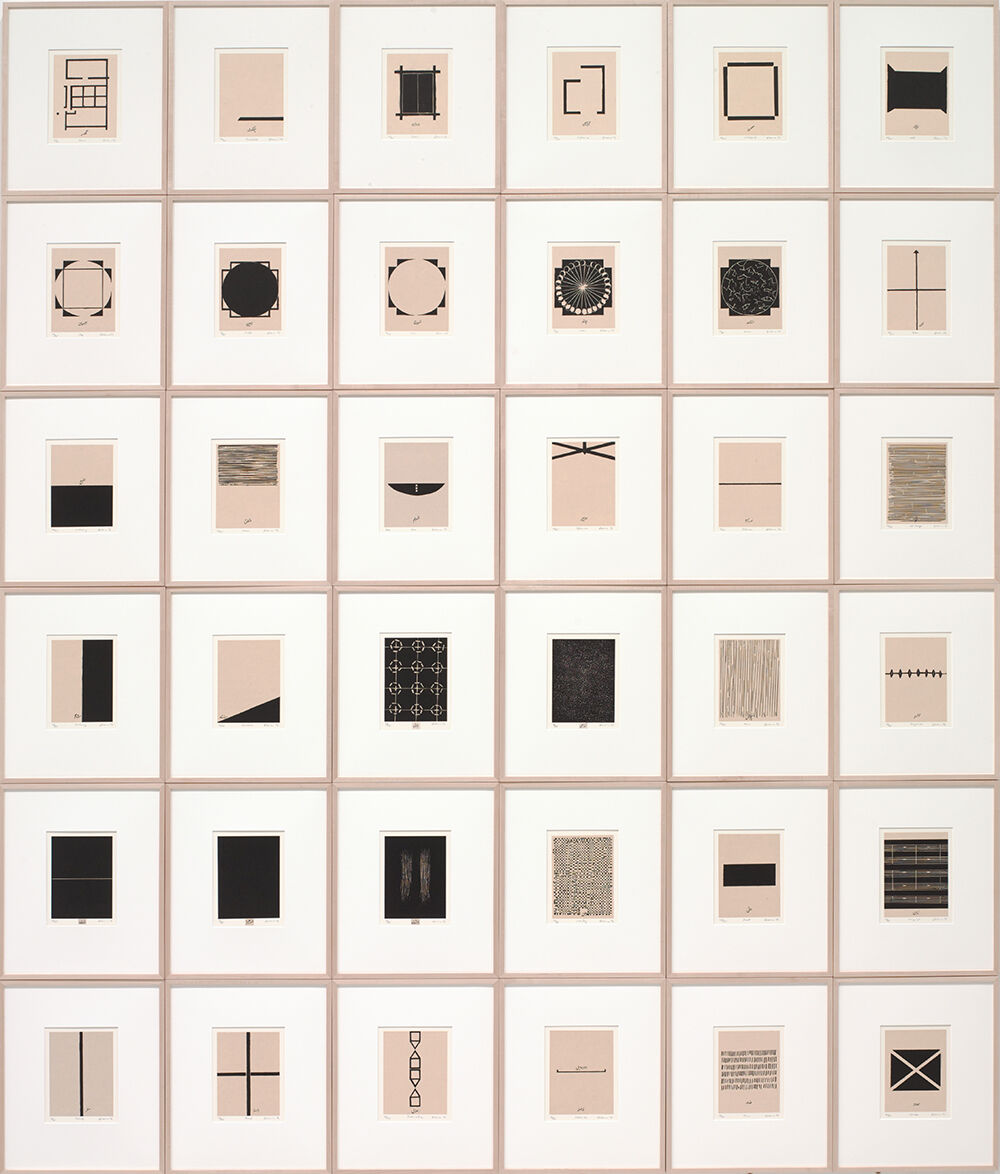

Zarina. Home is a foreign Place

Born in Aligarh, India, to a Muslim family, Zarina grew up aware of the political and religious struggles between her native country and neighboring Pakistan, a majority-Muslim state, which was partitioned from the majority-Hindu India in 1947 by the British. Zarina, once explained: “This piece is my narrative of the house I was born in and left in my early twenties never to return.”Home Is a Foreign Place consists of 36 woodblock prints, each of which presents a geometric, monochromatic design. To make these images, Zarina jotted down a list of Urdu words that she considered meaningful, such as “axis,” “distance,” “road,” and “wall.” She sent the list to a calligrapher in Pakistan, who wrote them in the traditional nastaliq script. Back in her New York studio, Zarina developed what she has described as “idea-images, which flowed from these words.” The resultant images serve as a visual vocabulary to express feelings of home, memory, and loss. “I understood from a very early age that home is not necessarily a permanent place,” Zarina said. “It is an idea we carry with us wherever we go. We are our homes.”

2. Art and Identity

“I paint my own reality.” — Frida Kahlo

“I try and look for an uninhibited moment, where people forget about trying to control the image of themselves.” — Rineke Dijkstra

Identity is the way we perceive and express ourselves. Factors and conditions that an individual is born with—such as ethnic heritage, sex, or one’s body—often play a role in defining one’s identity. However, many aspects of a person’s identity change throughout their life. People’s experiences can alter how they see themselves or are perceived by others. Conversely, their identities also influence the decisions they make: Individuals choose their friends, adopt certain fashions, and align themselves with political beliefs based on their identities.

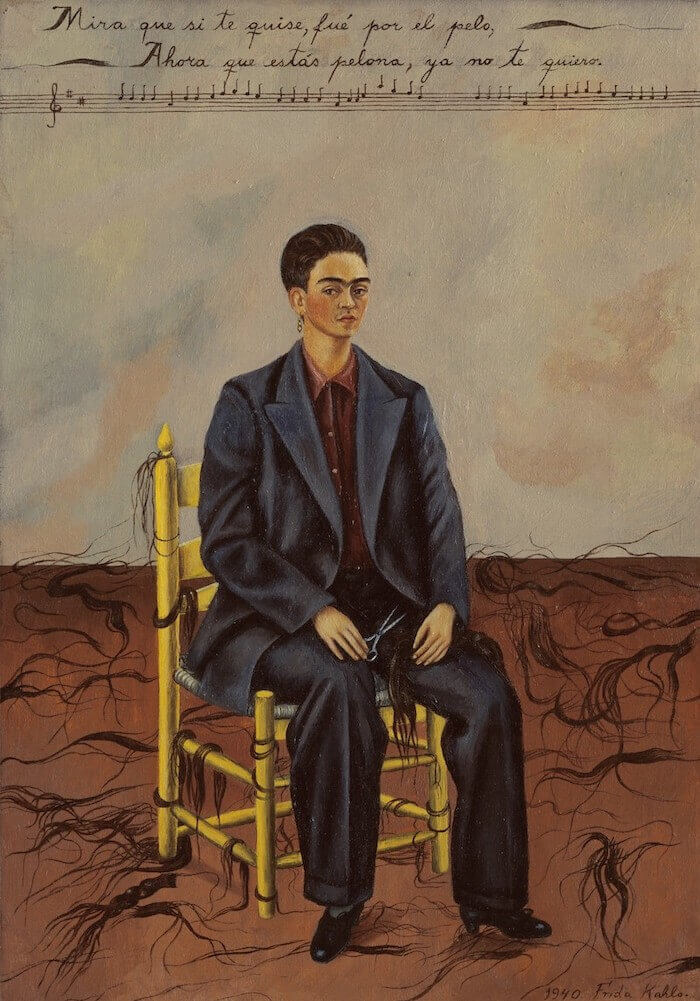

Frida Kahlo. Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair. 1940.

Though the Surrealists adopted Frida Kahlo as one of their own, the painter maintained that she did “not know if my paintings are Surrealist or not, but I do know that they are the most frank expression of myself.” She produced numerous self-portraits, each one an articulation of different facets of herself and her eventful life.Kahlo painted Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair in the wake of a particularly tumultuous time, just months after she divorced her famous husband, Mexican Muralist painter Diego Rivera. He had always admired her long, dark hair, which, as she indicates in the tresses littering the painting, she had cut off after their split. She also shows herself in an oversized suit resembling the ones that Rivera wore. Through such emotionally and symbolically charged details, Kahlo expresses her feelings about her relationship with Rivera while also asserting her sense of self as an independent artist.

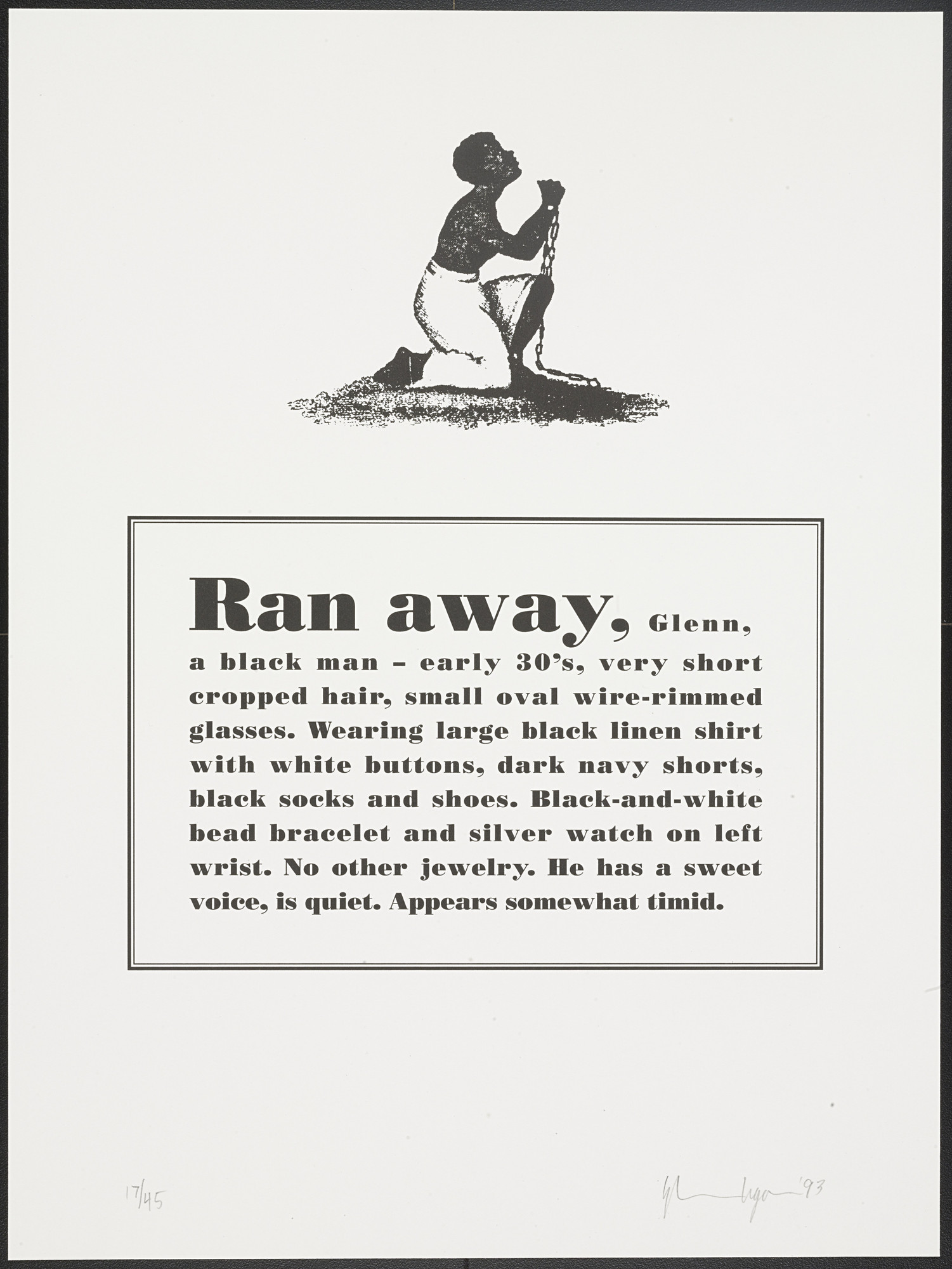

Glenn Ligon. Untitled, from Runaways. 1993

“If I have a well to dip into, it’s filled with almost four hundred years worth of permutations of what blackness has meant and speculations on what it might mean in the future,” Glenn Ligon has said about a body of work through which he challenges assumptions about identity.In Untitled (Runaways), he demonstrates how black American identity has been shaped by the history of slavery. Ligon began by asking 10 friends to imagine that he was missing and to provide descriptions that would help people find him. He included their portrayals in lithographs styled after two opposing historical documents: their layout mimics that of runaway slave posters from the early 17th to mid-19th centuries, while their illustrations and typeface come from 19th-century abolitionist publications. These descriptions also recall wanted ads for criminals, suggesting that the language of slavery aligns with the stereotyping and racial prejudice that mar some police practices today.

Andy Warhol. Gold Marilyn. 1962

In 1962, America was shocked by the news that actress and pop culture icon Marilyn Monroe had committed suicide. Pop art icon Andy Warhol soon got to work, immortalizing her in Gold Marilyn Monroe. He took a cropped image of her head from a 1953 publicity photograph and silkscreened it onto the center of a large canvas coated with gold paint. Her face floats in this gold field, overlaid with garishly colored, slightly off-register makeup.In this composition, Warhol collapses the tradition of Byzantine icon painting with the techniques of commercial advertising, suggesting that Monroe was a modern-day goddess created and commodified both by Hollywood and the viewing public. She personified American beauty, prosperity, and happiness, but the false construction of this idealized image came at the expense of her personal bouts with anxiety and depression. As Warhol once observed: “Everyone needs a fantasy.”

Pablo Picasso. Girl before a Mirror. 1932

In Girl before a Mirror, Picasso’s lover and muse, Marie-Thérèse Walter, engages with her reflection. This was one of numerous portraits—ranging from recognizable to abstract—that the artist made of his younger companion, who he met in the late 1920s. In this work, Picasso presents a multi-angled, multifaceted view of Marie-Thérèse. She stands nude (and possibly pregnant) before a mirror, her face comprised of two starkly differing halves: one fresh and serene, the other made-up in yellow, red, and green, as if to indicate the innocence and sensuality bound up within the same woman. The reflection in the mirror presents still another picture of Marie-Thérèse, which has been interpreted as her psyche, a darker doppelganger, or her aged self. While Picasso filled this canvas with the image of his lover, he also symbolically suggests his own presence through the lattice pattern covering its background, which recalls the costume of a Harlequin, a character that the artist identified with.

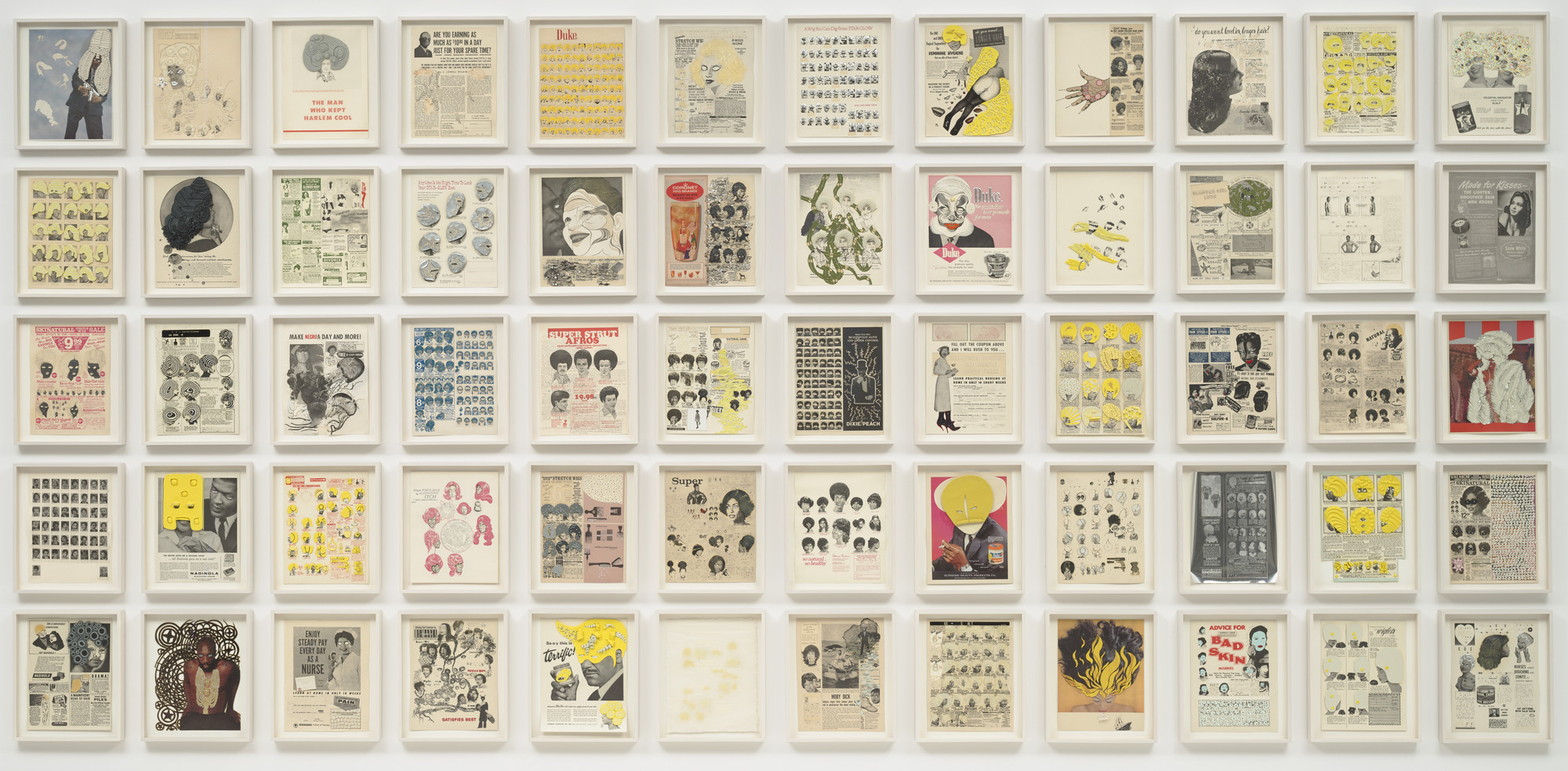

Ellen Gallagher. DeLuxe. 2004–05

Biting, humorous, and poignant, Ellen Gallagher’s DeLuxe is a deft commentary on race, racism, and identity, especially African and African American identity. To make this work, the artist drew from her collection of vintage magazines geared towards black audiences, including Sepia, Our World, and Ebony. She isolated 60 pages from these publications, focusing largely on advertisements for cosmetic products ranging from wigs to acne treatments to skin-bleaching creams. Using historical and contemporary printmaking techniques and a riot of materials—like velvet, toy ice cubes, and googly eyes—she altered the pages, emphasizing the messages of beauty, success, and self-worth they convey. She then individually framed the pages and arranged them into a grid, brimming with materials and detailed imagery. Among the messages Gallagher critiques are the belief that one's appearance can be improved through wigs and skin-lightening, and the notion that financial success can be achieved by attending nursing school or selling products door-to-door. The artist has described this piece as being “about identity in the most open sense of that word. No matter how uniform or how altered, it just refuses to be stamped out.”

Marc Chagall. I and the Village. 1911.

Marc Chagall was born and raised in a Hasidic Jewish village in Belarus. Judaism was fundamental for him: it shaped his identity and his work. Painted a year after he moved to Paris, I and the Village is a fairy tale evocation of home, resonant with nostalgia. The faces of a peasant—which has been interpreted as a self-portrait—and a cow frame a view onto a vividly colored scene, where a male figure carrying a scythe walks behind an upside-down woman. In the foreground, a flowering sprig seems to sprout from the peasant’s large hand, possibly referencing the tree of life. In Chagall’s village, people and animals lived in mutual dependence and according to the Hasidic belief that animals linked humankind to the universe. The dotted line connecting the eyes of the cow and peasant suggests this important relationship and the artist’s ties to his community and culture. “Cows, milkmaids, rooster, and provincial Russian architecture…are part of the environment from which I spring,” he once described.

Henri Matisse. The Red Studio. 1911.

Though Henri Matisse does not appear in The Red Studio, his presence is strongly suggested in this painting of his artwork-filled studio. He made this painting at a time of critical and financial success, when increasing demand for his work enabled him to build a new studio. Rather than faithfully depicting this workspace, he transformed its white walls into vivid red, flattened out its volumes, turning its furnishings into ghostly silhouettes, and replaced its more utilitarian contents with a display of his paintings, sculptures, and ceramics. These appear bright and detailed against the red interior, arranged around the central axis of a grandfather clock whose face has no hands. Time has stopped in this space, which is so closely connected with Matisse that it may be seen as a stand-in for the artist himself. The box of crayons in the foreground—his tools ready for use—further emphasizes his presence.

Rineke Dijkstra. Almerisa series. 1994–2008

Known for her psychologically rich portraits, Rineke Dijkstra was photographing Bosnian refugee children at an asylum center in the Netherlands, where she encountered and photographed six-year-old Almerisa Sehric. Revisiting this photograph two years later, Dijkstra was struck by its power. She sought out Almerisa and her family, who were by then living in their own apartment. And so began a sustained portrait series, for which Dijkstra photographs Almerisa every two years. “What you see in this series is…how she develops from a child from a foreign country into a Dutch young woman,” describes Dijkstra. “The chair represents my life […],” says Almerisa, referring to the increasingly solid chairs in which she is seated in every picture. “When I came to the Netherlands it was…unstable like the plastic chair, and now I’m sitting on a wooden chair with more stability, with my feet on the ground and holding my first-born child.”

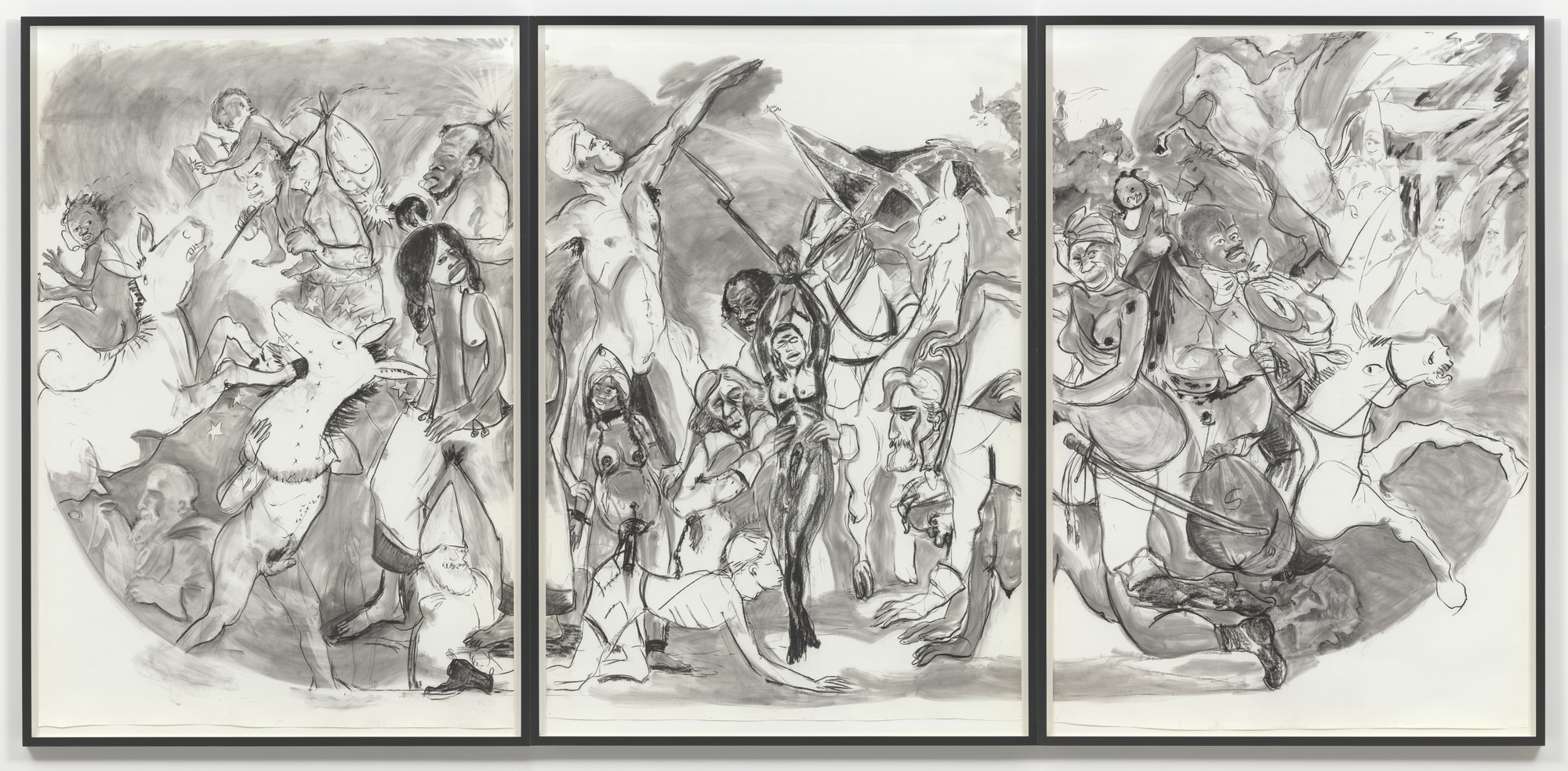

Kara Walker. 40 Acres of Mules. 2015.

Kara Walker creates historical allegories in which characters play out repulsive dramas of racial and gender bigotry with cool detachment and biting humor. This three-part drawing was inspired by a trip the artist took to Stone Mountain Park, outside Atlanta. Considered by some to be the spiritual home of the Ku Klux Klan, the park houses the infamous granite relief sculpture depicting three Confederate leaders of the Civil War: Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. Walker's large-scale drawing shows the generals and their horses, Klansmen, the Confederate flag, nude figures, and mules in a swirling, quasi-apocalyptic scene of domination and degradation. The central figure, a black man, his hands bound by rope, takes on the role of the martyr of Western history paintings. This work was made in 2015, a moment marked by Black Lives Matter, a mass mobilization to protest racial profiling and police brutality. The title refers to the undelivered reparations promised to emancipated slaves under the phrase "forty acres and a mule,"or land and an animal to work it. It also calls to mind the mule-led funeral procession for Martin Luther King, Jr., whose 1962 "I Have a Dream" speech proclaimed, "Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia!"

3. Transforming Everyday Objects

“As an artist, I think that I should work with processes and media that are immediately around me.” —El Anatsui

Many artists use everyday objects—like beds, bicycle wheels, and teacups—to challenge assumptions about what constitutes art and how it should be made. Designers develop useful objects considering form, function, and, often, beauty. This theme will introduce you to ideas about artistic and design choices, and the creative acts of inventing and transforming everyday objects.

Marcel Duchamp. Bicycle Wheel. 1951

Marcel Duchamp was a pioneer of Dada, a movement that questioned long-held assumptions about what art should be and how it should be made. In the years immediately preceding World War I, he found success as a painter in Paris. But he soon gave up painting almost entirely, explaining, “I was interested in ideas—not merely in visual products.” In this spirit, he began selecting mass-produced, commercially available, and often utilitarian items, designating them as art, and giving them titles.These “Readymades,” as he called them, disrupted centuries of thinking about the artist’s role as a skilled creator of original, handmade objects. Instead, he argued that “an ordinary object [could be] elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist.” Duchamp claimed he selected objects regardless of “good or bad taste,” defying the notion that art must be pleasing to the eye.

Marcel Duchamp’s concept of ready-mades significantly challenged traditional definitions of art in several ways:

- Rejection of Aesthetic Value: Duchamp emphasized that the choice of ready-mades was not based on aesthetic appeal. This contradicted the traditional view that art must be beautiful or skillfully crafted.

- Concept Over Craftsmanship: By presenting everyday objects, like a bicycle wheel on a stool, as art, Duchamp shifted the focus from the artist’s technical skill to the idea behind the work. This introduced the notion that art could be conceptual rather than purely visual.

- Viewer’s Role: Duchamp believed that a work of art was incomplete without the viewer’s perception and interpretation. This idea encouraged audiences to engage with art critically, asking questions about its meaning and purpose.

- Kinetic Sculpture: His ready-made of the bicycle wheel was intended to be spun, introducing movement and interaction, which expanded the definition of sculpture beyond static forms.

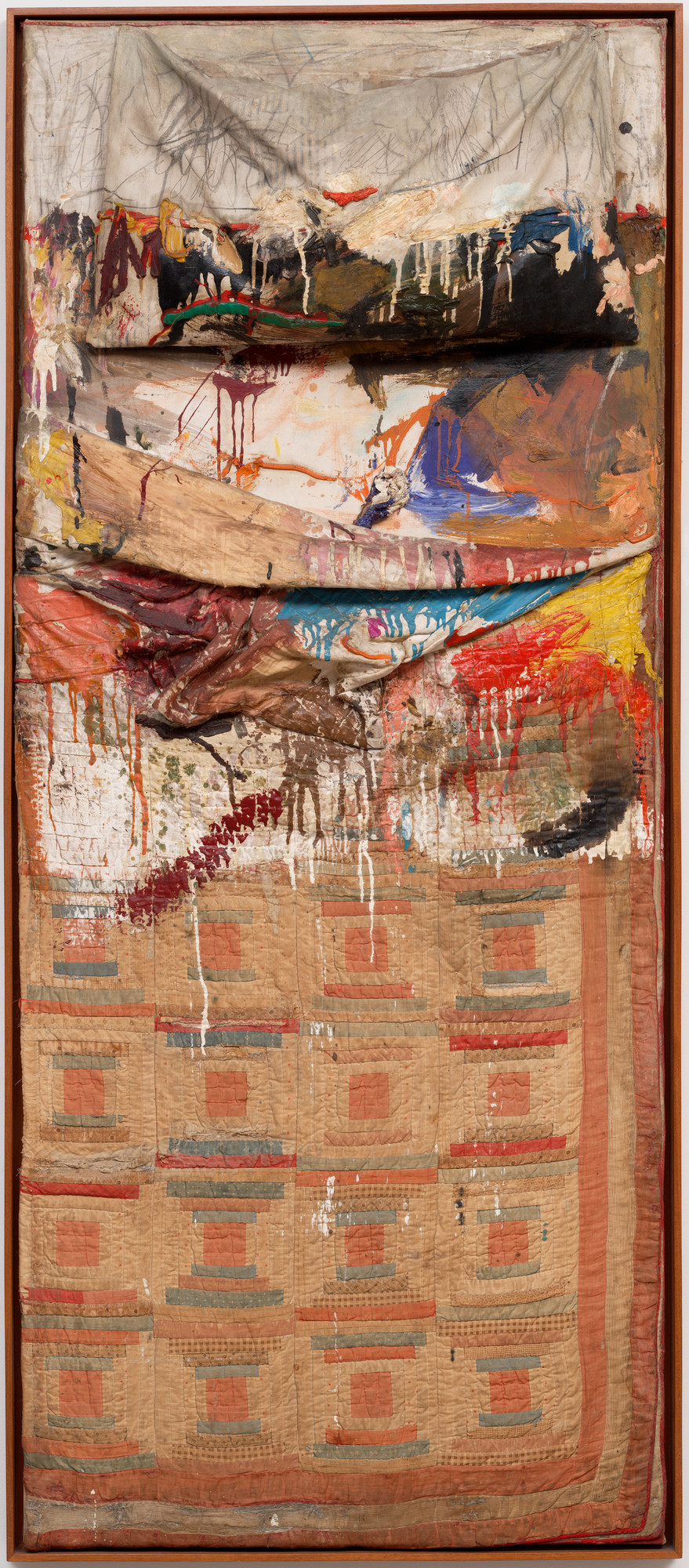

Robert Rauschenberg. Bed. 1955.

Though the Abstract Expressionists dominated the New York City art scene when Robert Rauschenberg was getting his start as an artist, he chose to rebel against these artists’ conception of their work as personal expressions of themselves, entirely separate from the outside world. He did this, in part, through works like Bed, which is one of his first “combines,” a term he coined to describe compositions combining elements of painting and sculpture and into which he incorporated such found objects as tires, furniture, trash, and even taxidermied animals. To make this work, Rauschenberg took a well-worn pillow, sheet, and quilt, attached them to wooden supports, and vigorously scribbled and painted on them (thereby lampooning Abstract Expressionist painting). Hung vertically on the wall like a traditional painting, Bed embodies the artist’s assertion that “painting relates to both art and life…I try to act in that gap between the two.”Blurring Boundaries: Rauschenberg challenges the traditional distinction between art and everyday objects. By using a quilt and a pillow, he transforms a mundane item into a work of art, prompting viewers to reconsider what constitutes art.

Meret Oppenheim. Object. 1936.

Artist Meret Oppenheim made a place for herself in the male-dominated Surrealist movement, whose members primarily regarded women as subjects of and muses for their work. Though she filled these roles for her male artistic peers, Oppenheim was also aware and critical of women’s place in both Surrealism and society. Her work is suffused with wry humor, eroticism, and darkness, reflecting her explorations of female identity and exploitation. To make Object, she wrapped a store-bought white teacup, saucer, and spoon in the fur of a Chinese gazelle, transforming items traditionally associated with decorum and feminine refinement into a confounding Surrealist sculpture. It caused a sensation when it was first exhibited and almost immediately became iconic. French poet and founder of Surrealism André Breton deemed it the perfect Surrealist object. The work exemplifies Breton’s argument that mundane things presented in unexpected ways had the power to challenge reason and to urge the inhibited and uninitiated (that is, larger society) to connect to their subconscious.This surrealist piece merges the familiar with the strange, evoking discomfort and intrigue while inviting viewers to reconsider the roles of domestic objects. It highlights themes of femininity and sexuality, prompting emotional responses and reflections on societal norms. Overall, it illustrates how art can provoke thought and challenge expectations.

Décolletage Plastique Design Team. Bic Cristal Ballpoint pen.1950.

While it may be easy to take for granted the ready availability and seemingly endless array of ballpoint pens today, it took ingenuity to think of such a thing in the first place. The first ballpoint pen was invented in 1938 by a Hungarian journalist who sought a better writing implement, through which ink could flow more regularly. Twelve years later, after a year of work by a team of designers at the French company Bic, the Bic Cristal® ballpoint pen was introduced to the marketplace. This was the company’s first ballpoint pen. Its co-founder, Marcel Bich, had invested in Swiss technology to allow his designers to craft the finest, most precise pen possible, which not only wrote well but also was comfortable to hold. After its initial success in France, the company took the pen to the American market in 1959, promoting it with the advertising pitch: “writes first time, every time.”The significance of design in everyday objects lies in its ability to enhance functionality, aesthetics, and user experience while reflecting cultural values.

Louise Nevelson. Sky Cathedral. 1958.

Louise Nevelson came from a family of lumber dealers and used wood in many of her works. Sky Cathedral—which has been likened to a Cubist composition, proto-installation art, and even a shrine—is comprised of nearly 60 stacked boxes filled with a riot of found wooden fragments. Some of these fragments are recognizable as furniture parts and architectural ornaments; others are the leftover scraps from larger projects. The loosely geometric grid formed by the boxes and its coating of black paint give structure and unity to this commanding, abstract assemblage of disparate parts. Like her Abstract Expressionist peers, Nevelson reached for spiritual transcendence in her work. But she was also engaged with the physical properties of her materials, as she has described: “Sometimes it’s the material that takes over; sometimes it’s me that takes over….It was always a relationship—my speaking to the wood and the wood speaking back to me.”

Mike Kelley. Untitled. 1990.

Stuffed animals, crocheted blankets, half-melted candles, and other found domestic and mass culture castoffs have become synonymous with Mike Kelley’s work. In Untitled, he aligned four handmade, vibrantly patterned afghan rugs on the floor and placed a hand-sewn stuffed doll in the center of each one. He incorporated such overlooked items into sculptural assemblages and installations that he insisted were about formal and intellectual concerns but into which most viewers and critics read themes of home, family, and childhood—both dysfunctional and idealized. Kelley used commonplace materials in order to draw our attention to and critique the larger culture surrounding us, as he once explained: “My interest in popular forms wasn’t to glorify them, because I really dislike popular culture in most cases. All you can do now, really, is…work with this dominant culture, I think, and flay it…rip it apart, re-configure it.”

Jessica Rosenkrantz, Jesse Louis-Rosenberg. Kinematics Dress.2013.

Designers and co-founders of Nervous System studio Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg merged nature and technology in their line of Kinematics garments, including the Kinematics Dress. This 3-D printed nylon dress is composed of thousands of individual triangular panels connected by hinges. Each dress is unique—shaped to a 3-D scan of the wearer’s body—and details including its length, patterning, and silhouette can be customized. After adjustments are made, the dress is printed in its entirety and ready for wear. For Rosenkrantz and Louis-Rosenberg, this process, with its lack of a fixed outcome, mimics the adaptive processes of development in nature and provides an alternative to (and perhaps eventually a replacement for) the uniformity of mass manufacturing. “Instead of creating…millions of items that are all the same, we’re creating something that maybe only just appeals to one person, but they can get that exact one thing that they want,” explains Louis-Rosenberg.

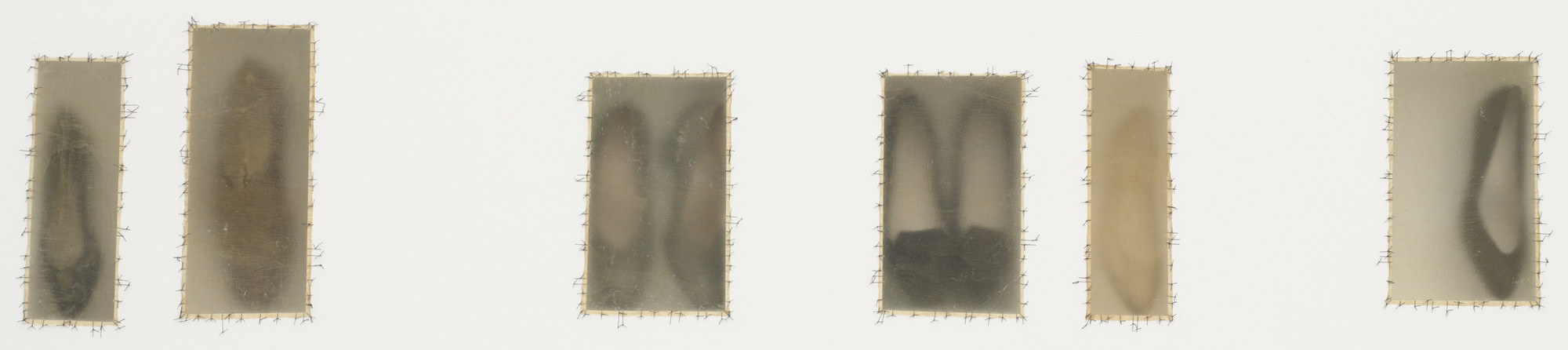

Doris Salcedo. Atrabilious. 1992–93.

Colombian artist Doris Salcedo describes herself as a “secondary witness” to the protracted civil war in her country and makes work that honors its hundreds of thousands of victims and that confronts those who perpetrate these conflicts. In Atrabilious (which means melancholy or ill temper) she encased worn women’s shoes, singly and in pairs, in niches covered over with a scrim made from stretched cow’s bladder. The shoes stand in for the people who have disappeared over the course of the conflict. Seen behind their murky, membranous coverings, the shoes appear as old photographs or saintly relics. “I cannot fix any problem[s]. I can do nothing. It’s a lack of power,” Salcedo has said. “But then as a person who lacks power, I face the ones who have power and who manipulate life. It’s from that perspective—of the one who lacks power—that I look at the powerful ones and at their deeds.”

4. Art and Society

“There is never such a thing as an apolitical or inert artwork.” — Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Many artists create work in response to the social, cultural, and political issues of their time. This theme offers a deeper understanding of history and contemporary society, and encourages you to think critically about world events and how they are depicted.

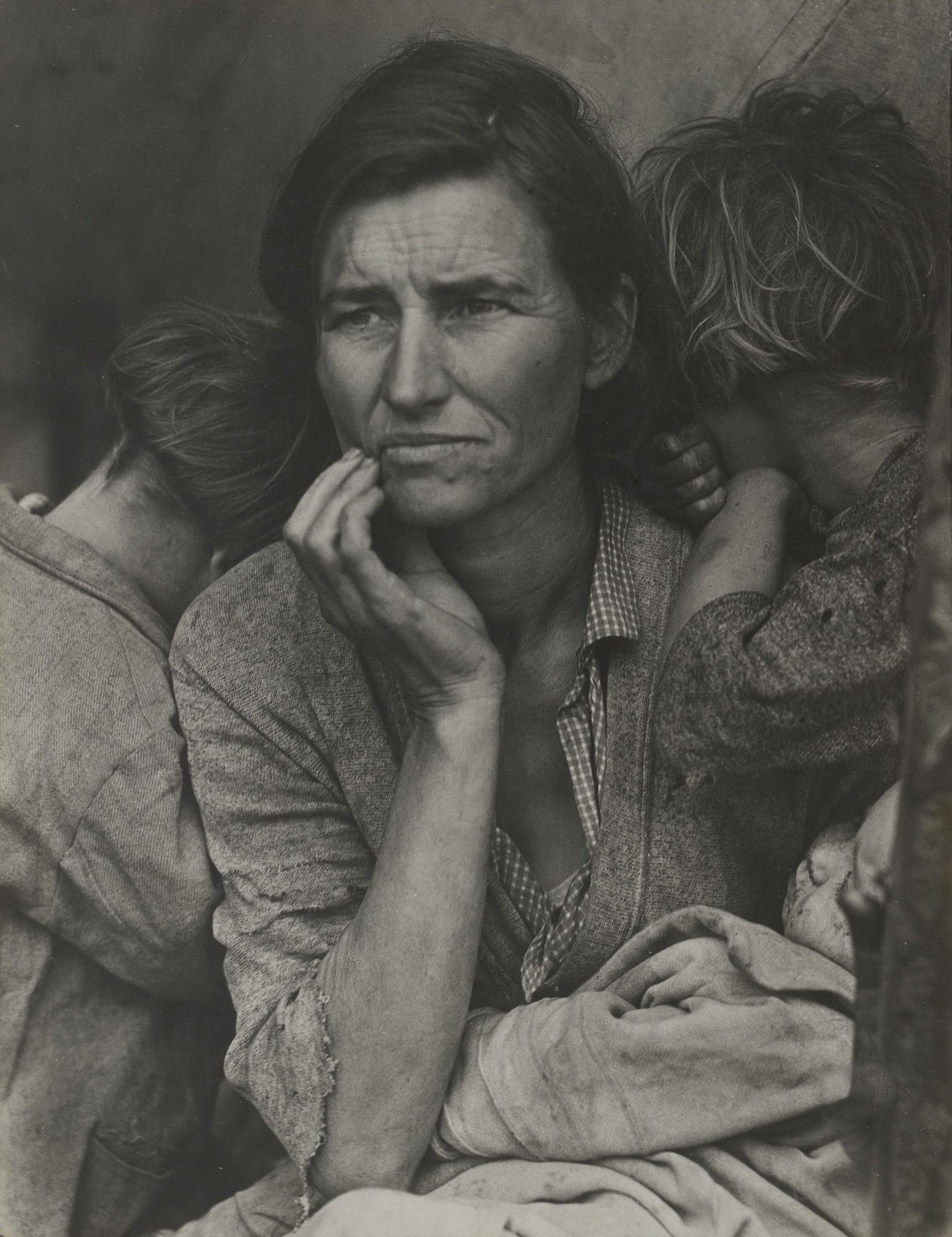

Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California. 1936.

Sometimes, a photograph’s compositional and emotional force captures the public and makes it an enduring symbol of a historical event. Such is the case with Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother. Almost immediately upon its publication in the San Francisco News in 1936, it was seen to encapsulate the plight of the masses of unemployed Americans during the Great Depression—and it remains an icon of this crisis to this day. Lange’s closely framed image centers on the worry-lined face of Florence Owens Thompson, a mother of seven who the photographer encountered near a camp of pea pickers beside devastated fields. A child stands on either side of her, their faces turned away from the camera. A baby wrapped in worn clothing rests in her lap. This composition has been compared to depictions of the Virgin and Child, a resemblance that triggers a similar moral sentimentality and that lends weight to its vision of suffering.

Jacob Lawrence. Migration Series. 1940–41.

Jacob Lawrence was the child of migrants who moved together with millions of other African-Americans from the impoverished rural South to industrialized Midwestern and Northeastern cities during the Great Migration. He came of age in Harlem, New York, a vibrant center of African-American life and culture. The textures of this neighborhood, and the narrative dynamism of the songs, sermons, and tales of his neighbors’ journeys north that he witnessed in church, shaped his approach to art making. After receiving a grant and researching for months at the 135th Street Library in Harlem, Lawrence made Migration Series. To distill the epic narratives of the Great Migration into powerfully direct images, he used descriptive titles, vibrant patterns and blocks of color, and pared-down, angular figures and forms, which unfold in tempera paint across sixty individual hardboard panels. He chose to focus on the people at the heart of the Great Migration, breaking apart this mass relocation of millions into intimate vignettes.

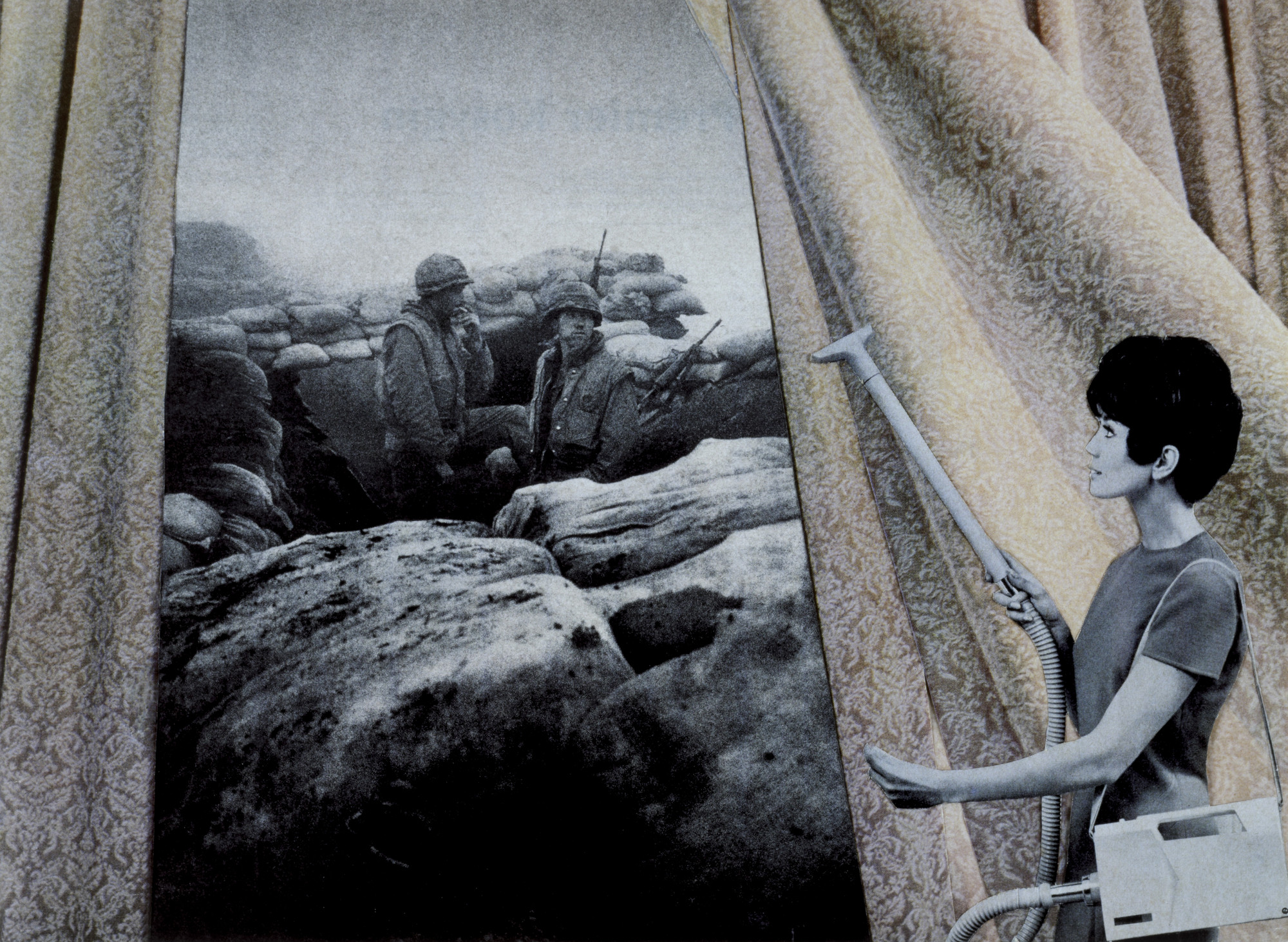

Martha Rosler. Cleaning the Drapes from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home. c. 1967–72.

Martha Rosler made House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home in protest against the Vietnam War—at a moment when American involvement in Vietnam had nearly peaked. To make these photomontages, she seamlessly combined images of the war with advertisements and illustrations of fashionable American home interiors, many published in the magazine, House Beautiful. By bringing together images of war and domesticity so that they appear to share the same space, she references the “living room war,” a phrase coined to characterize the Vietnam War as the first major military conflict to be extensively broadcast into people’s homes on television. “The series is called House Beautiful…because it really is centered on the idea of domesticity, safety, space, and aesthetic rightness,” she has explained. “But also Bringing the War Home because I am literally bringing images of the war into spaces having to do with our domestic life.” Rosler considered these images to be agitprop, originally disseminating them as photocopied flyers at anti-war demonstrations.

Jasper Johns. Flag. 1955.

When Jasper Johns made Flag—a mixed media painting of encaustic and pigment on newspaper clippings and canvas—Abstract Expressionism was dominant, the Cold War was entrenched, and the United States government was seeking out suspected Communists in the country’s midst during the Second Red Scare. At this charged time, the American flag was an especially potent symbol—both political and artistic. While the Abstract Expressionists had stripped painting of references to the real world, Johns boldly re-inserted into it one of the most recognizable symbols of all. He broke with the notion that painting was a means of abstract personal expression and incorporated into his work what he described as “things the mind already knows.” But he also carried forward abstraction in the gestural brushstrokes that break apart the flag’s surface into an elaborately textured field. One critic encapsulated this work’s ambivalence, asking: “Is this a flag or a painting?” It could be said to be both.

Shahzia Sikander. Candied. 2003.

Trained in the rigorous art of Indo-Persian miniature painting, Shahzia Sikander explores history, politics, religion, and identity in her own work. She simultaneously adheres to and subverts the strictures of this centuries-old artistic tradition, playing with its iconography and freely sampling imagery from a range of sources to challenge such polarities as Hindu and Muslim and East and West. In Candied, she places a tangle of bodies—male, female, animal, and possibly divine—in the center of a page stained with delicate washes of ink. Cascading disembodied silhouettes of the stylized hair of the Gopi women, worshippers of the Hindu god Krishna, overlay these figures. For Sikander, this is a playful and intentionally ambiguous image, with which she has said that she hopes to create “a gap, or a distance, or a break” in political, religious, and other fixed ideologies, opening up possibilities for uncertainty and the discovery of different perspectives.

Faith Ringgold. American People Series #20: Die. 1967.

Faith Ringgold made American People Series #20: Die in the late 1960s, when the United States was engulfed in race riots. Unsettled by the fact that the media was barely covering the riots, and inspired by Pablo Picasso’s powerful depiction of the horrors of the Spanish Civil War in his painting, Guernica (1937), she decided to use art to document her own troubled times. “One of the most difficult things that I ever painted in my life was this picture, because of the blood,” she recalled. “If [the media] did show a photograph…of any kind of riot, they never showed the blood…So I wanted to make sure that I put the blood in there, because I knew that blood meant death, and that’s what happened at those riots.” Across this large-scale painting, she depicts a frenzied spectacle of violence. Professionally dressed black and white men and women bloody each other with weapons and their own hands. Two children—a black girl and a white boy—cower underfoot, clinging to each other. With this scene, Ringgold addressed the fraught race relations of the 1960s and expressed her fear that racial violence would continue into the future. “So now what do we have…in 2016,” she asked. “It just goes on and on, the violence.”